Retirement Tax Incentives Are Ripe for Reform

Current Incentives Are Expensive, Inefficient, and

Inequitable

By Chuck

Marr, Nathaniel

Frentz, and Chye-Ching

Huang

December 13, 2013 - Center on Budget and Policy Priorities

Costing well over $100 billion a year, tax incentives for retirement plans

such as pensions, 401(k)s, and individual retirement accounts (IRAs) are one of

the largest federal tax expenditures. Yet they appear to do little,

relative to their high cost, to accomplish their goal of encouraging new

saving.

The main reason is that the bulk of their benefits go to higher-income

households; in 2013, some 66 percent of the benefits of the retirement tax

incentives went to the 20 percent of taxpayers with the highest incomes.

These higher-income taxpayers are likely to save substantial amounts

anyway for retirement and other purposes, and they are likely to

respond to retirement tax incentives primarily by shifting existing assets into

tax-preferred accounts rather than by undertaking additional saving.[1]

Meanwhile, the bottom 20 percent of households receive just 2 percent

of the benefits of retirement tax incentives, even though low-income people are

the least likely to have savings and the most likely to need tax incentives to

save for retirement (see Figure 1). To ensure sufficient savings during

retirement, therefore, current tax incentives are poorly targeted and

inefficient.

Retirement Tax Expenditures Are Expensive

The primary retirement savings incentives allow people to contribute to

retirement accounts, such as a traditional 401(k) or IRA plan, on a pre-tax

basis. That is, taxpayers can defer all taxes on retirement contributions

and earnings until they withdraw the money in retirement,[2] at which point it is taxed as ordinary income.

Part of the reason that this subsidy is substantial is that average tax rates tend to

be lower in retirement, both because on average, retirees have less income than

before retirement, and because Social Security income is taxed at lower rates

than are wages and salaries. A person generally needs less income in

retirement to maintain the same standard of living, in part because itfs no

longer necessary to save for retirement or pay work-related expenses, and also

because most people who are retired donft incur substantial child-rearing costs.

(The principal exception is in the health care area; a small percentage of

retired people can face catastrophic health care costs as a result of the lack

of a limit in Medicare on out-of-pocket costs and the costs that people can face

for nursing home or other institutional care.)

With gRothh IRAs and Roth 401(k)s, the tax treatment is reversed:

contributions are taxed, but neither the growth of the assets in these

accounts over time as they produce earnings, nor the withdrawals made in

retirement, are subject to tax. Taxpayers choose the type of retirement

vehicle that benefits them most over time. For example, they will likely

choose a Roth-type account rather than a traditional account if their tax

savings in retirement will exceed their upfront tax payments.

The total of all assets in defined contribution and IRA retirement plans is

estimated to be over $10 trillion in 2013.[3]

The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimates[4] that tax breaks for retirement contributions and

earnings will be the second-largest tax expenditure over the next decade,

costing $137 billion in 2013 and $2 trillion over 2014-2023. These

estimates are based on January 2013 figures from the Joint Committee on

Taxation, which estimated the revenue loss from individual tax provisions as

shown in Table 1.[5]

By CBOfs estimate, these incentives will cost the federal government more

than all veteransf programs combined — from veteransf disability compensation

and veteransf pensions to veteransf health care, which together will cost $1.7

trillion over the decade. They will also cost more than the costs of the

Departments of Transportation and Education combined ($1.6 trillion over the

decade).

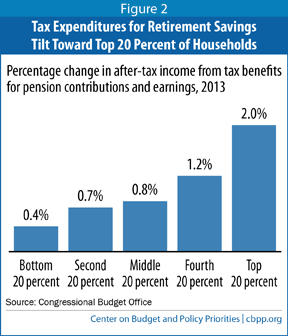

Subsidies gTilt Heavily Toward the Top,h According to CBO

The benefit from the deferral on retirement contributions is tied to a

taxpayerfs marginal tax rate and thus rises as household income increases.

For example, someone making $40,000 and in the 10 percent tax bracket

receives an upfront tax subsidy of 10 cents per dollar of deductible retirement

contributions, whereas someone who makes $450,000 and is in the 35 percent

bracket receives an upfront subsidy of 35 cents on the dollar.

As

a result, the benefits from retirement savings tax expenditures gtilt heavily

toward the top,h as a recent CBO report explains.[6]

- The top 20 percent of households receive nearly twice as much in

retirement tax subsidies as the bottom 80 percent combined.

- As a share of income, the subsidies are worth on average 2½ times as

much for the people in the top fifth of households as for the people in

the middle fifth, and five times as much as for the people in the bottom fifth

(see Figure 2).

Contribution Limits Affect a Small Percentage of Workers

The tax code limits the amounts that taxpayers (and employers on behalf of

their workers) can contribute to tax-preferred savings accounts each year. These

contribution limits have become considerably more generous as a result of the

Bush tax cuts,[7] which raised the limits and allowed additional

gcatch-uph contributions for people aged 50 and above. In 2013, a worker

can put $17,500 into a 401(k) tax-free ($23,000 if the worker is 50 or older).[8] But the employer can make its own contributions,

and the combined employee and employer limit is $51,000 ($56,500 if the worker

is 50 or older). The annual contribution limit to IRA accounts is $5,500

($6,500 for people aged 50 or older). (See Table 2.) Deposits to

defined-benefit pension accounts (as opposed to defined-contribution plans, such

as 401(k)s) are also tax free.

These

increases in the contribution limits overwhelmingly benefit people high on the

income scale, for three reasons. First, most other Americans who

contribute to retirement accounts contribute much smaller amounts and donft

approach the limits. The Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center has noted that

the increase in the contribution limits enacted over the past decade gbenefit

few workers because most contribute well below the old maximum.h[9]

Second, the higher an individualfs tax bracket, the greater the tax

subsidy that he or she receives for contributions.

The third reason that the benefit of the higher contribution limits is so

skewed to the top is that only about half of families even have retirement

accounts,[10] and higher-income families are far more likely to

have such accounts than families lower on the income scale, as Figure 3 shows.

Low- and modest-income workers tend to have less access to work-based

retirement plans,[11] either because their employer does not offer a plan

or because they may work part time and donft qualify for their employerfs plan.

In addition, those low- and modest-income workers who do have access to

work-based plans tend to participate less often,[12] in part because they often live paycheck to paycheck

and feel they canft afford to make retirement contributions out of their modest

earnings, and in part because the tax subsidies they receive for retirement

contributions are small.

Among

workers who participate in retirement plans, only a small percent are

constrained by contribution limits. Only 5 percent of participants

contribute the maximum amount to a 401(k),[13] and those are primarily the participants with higher

incomes, as Figure 4 shows.[14] (The percentage of IRA participants making the

maximum contribution to an IRA is higher, but only 7 percent of all workers

participate in such plans.[15] )

The impact of the current, high contribution limits remains heavily skewed by

income when one looks at workers overall, as Figure 5 indicates, just as when

one looks at workers who participate in such plans.

Moreover, those investors who are constrained by the contribution

limits face no restrictions on the total amount of money that can accrue within

retirement accounts on a tax-deferred basis (as the example of Governor Romney[16] illustrated). Indeed, some investment

strategies can result in extremely affluent individuals receiving high returns

on large sums placed in such accounts that far exceed the returns that more

conventional types of investments generate. For example, some private

equity firms have allowed employees to use tax-deferred retirement accounts to

acquire interests in investment partnerships at a significantly lower valuation

than the fair market value.[17] When the investments are successful, the value

of the interests can explode; the Wall Street Journal reported last

year on one private equity co-investor who reportedly saw a 583-fold increase in

the value of an IRA investment.[18] These strategies can result in IRAs worth tens

of millions of dollars.[19] Such cases represent loopholes around the

already generous contribution caps and can result in runaway tax shelters.

Income Limits on Roth IRA Contributions Are of Limited Effectiveness

For workers who participate in a retirement plan at work, there are income

limits on the deductions for contributions made to a traditional IRA. These

limits phase out the tax deduction between $59,000 and $69,000 in income for

single filers, and between $95,000 and $115,000 in income for couples.[20]

The amount that can be contributed to a Roth IRA also phases out with

income — between $112,000 and $127,000 in income for single filers and between

$178,000 and $188,000 in income for couples.[21]

Individuals with incomes above these income limits, however, can shift large

sums (even their entire account balances) from 401(k)s and other accounts that

donft have income limits to a traditional or Roth account. They

can also shift funds from a traditional IRA to a Roth IRA. In the case of

a Roth conversion, taxes are owed on the amounts shifted into a Roth IRA, but

all subsequent earnings on the account — and all withdrawals after five years —

are entirely tax free. Such conversions can provide individuals with income far

above the income limits with an opportunity to reduce their taxes through the

Roth structure, particularly by shifting investments with the potential for a

high rate of return from accounts in which future earnings will be subject to

tax into accounts where all future earnings are tax free.

Another benefit that Roth IRAs provide to high-income households is that they

do not require any distributions based on age, unlike

other tax deferred plans such as 401(k)s and traditional IRAs, which require

people to start taking distributions from the accounts no later than age

70½.

As a result, converting large balances from 401(k) accounts to Roth accounts

can enable wealthy individuals to pass on more wealth to their heirs.[22]

Evidence Shows Low-Income Households Are the Least Prepared for

Retirement

Although high-income households receive the greatest tax incentives,

low-income households face the greatest need for additional retirement

saving. Studies find that lower-income households are, on average, much

less prepared for retirement than higher-income households (see box).

Studies Find Greatest Savings Inadequacy Among Low-Income Households

There is no consensus on the best way to measure and estimate the adequacy

of household retirement-savings,a but studies using a variety of

methods consistently find that lower-income households are much less prepared

for retirement than higher-income households and that a highly

disproportionate share of the households with inadequate retirement savings

are found in the lower part of the income distribution:

- Karl Scholz of the University of Wisconsin and colleaguesb

have estimated whether people are saving goptimallyh for retirement — that

is, making the best use of their earnings during their working years to

enable them to smooth out their consumption spending over their lifetimes.

This study finds that the households at the bottom of the lifetime

earnings distribution are those most likely to have savings below their

optimal targets, and that (as Figure 1 of this paper illustrates), the

majority of those with suboptimal savings are found in lower income groups.

Eric Engen and colleagues have also used a glifecycleh approach and

found a similar pattern.c

- The Employee Benefit Research Instituted (EBRI) measures

whether a householdfs savings are sufficient to allow a benchmark level of

consumption spending in retirement, based on the householdfs prior

consumption and the expected cost of long-term care. This method

shows a greater total percentage of households with inadequate retirement

savings than the Scholz analysis does — and an even starker divergence

between low- and high-income households.

- The Center for Retirement Research at Boston Collegee compares

householdsf projected incomes with an assumed target amount needed to

maintain their pre-retirement standard of living in retirement. This

approach, which finds the highest total share of households with inadequate

retirement savings among the three analytical approaches noted here, also

shows that lower-income households are the least

prepared.f

a Congressional Budget Office, gBaby Boomersf

Retirement Prospects: An Overview,h November, 2003, http://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/cbofiles/ftpdocs/48xx/doc4863/11-26-babyboomers.pdf.

b Karl Scholz, Ananth Seshadri, and Surachai Khitatrakun, gAre

Americans Saving eOptimallyf for Retirement?h Journal of Political

Economy, 2006, vol. 114, no. 4, http://www.ssc.wisc.edu/~scholz/Research/Optimality.pdf.

c Eric M. Engen, William G. Gale, and Cori E. Uccello,

gLifetime Earnings, Social Security Benefits, and the Adequacy of Retirement

Wealth Accumulation,h Social Security Bulletin, Vol. 66 No. 1, http://www.ssa.gov/policy/docs/ssb/v66n1/v66n1p38.pdf.

d Jack VanDerhei, gRetirement Income Adequacy for Boomers and

Gen Xers: Evidence from the 2012 EBRI Retirement Security Projection Model,h

Employee Benefit Research Institute, EBRI Notes Vol. 33, May, 2012, http://www.ebri.org/pdf/notespdf/EBRI_Notes_05_May-12.RSPM-ER.Cvg1.pdf.

e

Alicia H. Munnell, Anthony Webb, and Francesca Golub-Sass, gThe National

Retirement Risk Index: An Update,h Center for Retirement Research, October,

2012, http://crr.bc.edu/briefs/the-national-retirement-risk-index-an-update.

f

EBRI attributes much of the difference between its results and those of the

Center for Retirement Research to EBRIfs incorporation of recent trends in

retirement savings vehicles such as automatic enrollment and escalating

contributions.

Tilt Toward High-Income Taxpayers Is Economically Inefficient

Beyond the stark inequity in subsidies and in the need for more substantial

retirement savings, the retirement tax subsidies also are economically

inefficient, because they largely subsidize behavior that would happen anyway.[23]

These subsidies increase personal saving only to the extent that they lead

people to increase their retirement contributions by consuming less or working

more, not by simply shifting existing assets from other savings or investment

vehicles into tax-preferred accounts. The subsidies thus are gupside

downh: they provide the largest subsidies to the people who are least

likely to increase their savings in response and most likely to respond to

the tax incentives by shifting savings from non-tax-preferred

investment vehicles to tax-preferred accounts. As a Brookings Institution

analysis explains, g[h]igh-income individuals are precisely the ones who can

respond to such tax incentives by reshuffling their existing assets into these

accounts to take advantage of the tax breaks, rather than by increasing their

overall level of saving.h[24]

Low-income households, on the other hand, generally have little existing

savings to shift. Accordingly, they are the group among whom nearly all

retirement contributions induced by tax incentives represent new savings.

But perversely, they are the people whom the current retirement tax

incentives benefit the least, if at all.

As the Congressional Research Service (CRS) finds, g[p]roposals that increase

retirement saving among low- and moderate-income workers could be effective in

increasing new saving because these workers typically have little or no

nonretirement saving to [shift to tax-preferred accounts].h[25] Several studies of pilot programs have shown

that additional savings tax incentives directed at low-income people are

modestly effective at increasing their savings, but only when the subsidy levels

for these people are higher than current law provides.[26]

Because the bulk of current retirement tax benefits go to high-income

taxpayers who are more likely to shift assets than to save more, the current

system does a poor job of increasing private saving and is highly inefficient.

When it comes to boosting national saving (a broader measure that

consists of saving by households, businesses, and the government — and that

reflects private saving minus government deficits or plus

government surpluses), the current system fares even worse. The large

costs of the retirement tax subsidies add to the federal deficit, so the current

system may actually reduce net national saving. As CRS has

concluded, g[c]onventional economic theory and empirical analysis do not offer

unambiguous evidence that these tax incentives have increased personal or

national saving.h[27] This is a devastating judgment, given the high

cost of these subsidies.

Conclusion

Current tax incentives for retirement saving are expensive, inequitable, and

economically inefficient, giving the largest subsidies to the people who least

need help in saving adequately for retirement and are most able to shift assets

to capture the subsidies. These subsidies are ripe for reform that can

help accomplish two important goals — raising revenue for deficit reduction and

tax-reform goals, and improving retirement saving incentives for low- and

moderate-income households, the groups with the most people who need to boost

their retirement assets. [28]

End notes:

[1] Eric M. Engen and William G. Gale, gThe effects of 401(k)

plans on household wealth: Differences across earnings groups,h Working Paper

8032, December 2000, http://www.nber.org/papers/w8032,

and Daniel Benjamin, gDoes 401(k) eligibility increase saving? Evidence from

Propensity Score Subclassification,h April 2005, http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=696363.

[2] Distributions made before the recipient reaches age 59 ½

from accounts funded by pre-tax contributions are taxed at ordinary rates and

subject to an additional 10 percent penalty, though some exceptions apply, such

as withdrawals for hardships, education, and buying a first home.

[3] Barbara A. Butrica, gRetirement Plan Assets,h Urban

Institute, April, 2013, http://www.urban.org/UploadedPDF/412622-Retirement-Plan-Assets.pdf.

[4] CBO states that the tax expenditure is g[d]efined as the

difference between the current treatment of pension contributions and income and

the treatment under a pure individual income tax in which contributions were

made with after-tax income, investment earnings inside pension accounts were

taxed like ordinary investment earnings, and pension distributions were

tax-free.h Congressional Budget Office, gThe Distribution of Major Tax

Expenditures in the Individual Income Tax System,h May 29, 2013, p. 16, http://www.cbo.gov/publication/43768.

[5] CBOfs aggregate estimate isnft comparable to the estimates

from JCT in that it includes the effects of retirement tax breaks on payroll tax

revenues as well as income tax revenues. Some tax expenditures related to

saving reduce both income subject to the income tax and earnings subject to

payroll taxes. Specifically, employer contributions to retirement and

pension accounts are not subject to payroll taxes and reduce earnings that would

be subject to the payroll tax.

[6] Congressional Budget Office, gThe Distribution of Major

Tax Expenditures in the Individual Income Tax System,h May 29, 2013, http://www.cbo.gov/publication/43768.

The tax benefits from current retirement contributions occur over many

years. Note that CBOfs standard estimates presented here for pension

expenditures are based on the impact of all current and past contributions on

current tax revenues. CBO states that under an alternative calculation

that estimates the effects of current contributions on current and future taxes,

the distribution of benefits gdoes not differ greatly.h

[7] Economic Growth and Tax Relief Reconciliation Act of

2001.

[8] Internal Revenue Service, gCOLA Increases for Dollar

Limitations on Benefits and Contributions,h http://www.irs.gov/Retirement-Plans/COLA-Increases-for-Dollar-Limitations-on-Benefits-and-Contributions.

[9] Tax Policy Center, gTax Topics: Pensions and Retirement

Savings,h http://www.taxpolicycenter.org/taxtopics/Retirement-Saving.cfm.

[10] Ana M. Aizcorbe, Arthur B. Kennickell, Kevin B. Moore,

and John Sabelhaus, gChanges in U.S. Family Finances from 2007 to 2010: Evidence

from the Survey of Consumer Finances,h Board of Governors of the Federal

Reserve Board, June 2012, http://www.federalreserve.gov/pubs/bulletin/2012/pdf/scf12.pdf.

[11] Bureau of Labor Statistics, National Compensation

Survey, Employee Benefits in the United States, July 2013, p 6, http://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/ebs2.pdf.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Congressional Budget Office, gUse of Tax Incentives for

Retirement Saving in 2006,h October 14, 2011, http://www.cbo.gov/publication/42731.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Edward Kleinbard and Peter Canellos, gWhy Wonft Romney

Release More Tax Returns?h CNN, July 18, 2012.

[17] Mark Maremont, gBain Gave Staff Way to Swell IRAs by

Investing in Deals,h Wall Street Journal, March 29, 2012, http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052970204062704577223682180407266.html.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Ibid.

[20] Internal Revenue Service, g2013 IRA Deduction Limits —

Effect of Modified AGI on Deduction if You Are Covered by a Retirement Plan at

Work,h http://www.irs.gov/Retirement-Plans/2013-IRA-Deduction-Limits-Effect-of-Modified-AGI-on-Deduction-if-You-Are-Covered-by-a-Retirement-Plan-at-Work.

[21] Internal Revenue Service, gAmount of Roth IRA

Contributions That You Can Make For 2013,h http://www.irs.gov/Retirement-Plans/Amount-of-Roth-IRA-Contributions-That-You-Can-Make-For-2013.

[22] Internal Revenue Service, gRetirement Plans FAQs

regarding Required Minimum Distributions,h http://www.irs.gov/Retirement-Plans/Retirement-Plans-FAQs-regarding-Required-Minimum-Distributions.

[23] Raj Chetty, gActive vs. Passive Decisions and Crowd-Out

in Retirement Savings Accounts: Evidence from Denmark,h NBER Working Paper No.

18565, November 2012.

[24] William G. Gale, Jonathan Gruber, and Peter R. Orszag,

gImproving Opportunities and Incentives for Saving by Middle- And Low-Income

Households,h The Hamilton Project, Discussion Paper 2006-02, April 2006, p. 12,

http://www.brookings.edu/~/media/research/files/papers/2006/4/saving%20gale/200604hamilton_2.pdf.

[25] Thomas L. Hungerford and Jane G. Gravelle, gCRS Report;

IRAs: Issues and Proposed Expansion,h Congressional Research Service, February

2, 2010, http://www.aging.senate.gov/crs/pension38.pdf.

[26] See Esther Duflo et al., gSaving Incentives for

Low- and Middle-Income Families: Evidence from a Field Experiment with H&R

Block,h The Quarterly Journal of Economics, November 2006; gThe $aveNYC

Account, Innovation in Asset Building, Research Update December 2010,h NYC

Office of Financial Empowerment, December 2010; gThe Importance of Tax Time for

Building Emergency Savings: Major Findings from $aveNYC,h UNC Center for

Community Capital, April 2013; and Gilda Azurdia, Stephen Freedman, Gayle

Hamilton, and Caroline Schultz, gEncouraging Savings for Low- and

Moderate-Income Individuals: Preliminary Implementation Findings from the

SaveUSA Evaluation,h MDRC, April 2013.

[27] Thomas L. Hungerford and Jane G. Gravelle, gCRS Report;

IRAs: Issues and Proposed Expansion,h Congressional Research Service, February

2, 2010, http://www.aging.senate.gov/crs/pension38.pdf.

[28] Reforming retirement incentives will be the topic of a

forthcoming CBPP paper.